Quilts and Art History – by Bill Volckening

In 1971, quilts gained international attention when the Abstract Design in American Quilts exhibition opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The exhibition signaled the arrival of a new appreciation for quilts. People who were accustomed to seeing quilts on beds saw them displayed on the walls of a museum, and recognized them as valuable works of art.

Since then, quilts have become more widely accepted by museums, but it’s still an uphill battle. And when it comes to the inclusion of quilts in the academic world, art history curriculum is lagging far behind the museums. I studied art history for six years in college and grad school, and there was never any mention of quilts. It wasn’t like I had a bad education – it was really the best education money could buy.

In my first semester at Rhode Island School of Design, Art History Professor Dr Barry Kirschenbaum took the podium and shared his foundation for evaluating each and every object of art. Dr. Kirschenbaum’s three most important criteria were iconography, function, and style. He told us to remember it, and I did.

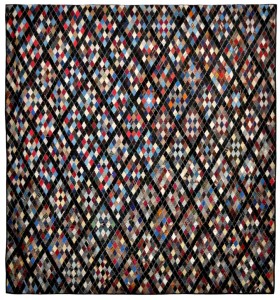

Silk diamonds quilt, c. 1890, eastern U.S., possibly Pennsylvania. This is the type of piece that makes me want to see quilts included in art history curriculum. It transcends the form, and reminds me of a diamond stained glass window.

Much time was spent in art history class discussing iconography, the branch of art history which studies the identification, description, and the interpretation of the content of the images; and style, such as impressionism or cubism. Very little time was spent on function, though. It was because the art history curriculum was structured around the three most validated and commodified forms of visual expression – the big three – painting, sculpture, and architecture.

At the time, art history was just beginning to address subjects like the history of photography. Quilts were not included in the curriculum because they were considered to be in the realm of craft or the decorative arts. They were also terribly undervalued as commodities. A painting could sell for a million dollars, and many have, but no quilt has ever approached that amount. The Reconciliation Quilt sold for $264,000 in a 1991 Sotheby’s auction, and that’s the all-time record amount for a quilt. Most quilts still sell for under $1000.

“Museums have had to fight the uphill battle of collecting objects not necessarily validated by the marketplace,” said Shelly Zegart in episode six of Why Quilts Matter – How Quilts Have Been Viewed and Collected. “While many of the country’s great museums mount the occasional quilt exhibition, those numbers are dwarfed by the number of shows of painting, furniture, glass, porcelain and other media. Turns out that quilts have a few strikes against them.”

Bernie Herman, Professor of American Studies at UNC Chapel Hill offers some possible reasons why quilts continue to face an uphill battle for acceptance among museum curators.

“I think that the problem is that, by virtue of what it is – what a quilt is, and its historical association – it suffers four damnations in the context of American art,” said Herman. “Quilts are associated with the domestic – domestic work, household work; quilts are associated with the work of women, often in the domestic sphere; quilts are associated with craft – that they exist outside of the kinds of artistic ideologies and politics of what we tend to think of as art; and that quilts are rooted in the world of the everyday. And so, in a sense they are alienated from art, they do not exist as an art form commodified in the contemporary art world.” Herman goes on to say quilts have always had a “really hard battle.”

When we talk about preserving and maintaining the heritage of quiltmaking in America, most people think of ideas such as teaching a younger person to make a quilt – but there’s more than one way to pass the tradition along to future generations. There was no such thing as quilt history class when I was in college, and I want to change that. The arrival of Why Quilts Matter tells me the time is right for quilts to gain greater acceptance, and not just in the museum world. Having quilts in museums is good, but in my opinion, seeing quilts appear in art history books and college curriculum would be even better.

Bill Volckening

Portland, Oregon

http://www.billvolckening.com

Image Credits:

Photo courtesy of Bill Volckening.